So every district you teach at, and every curriculum you use will have variations in pacing. Sometimes, you’ll 100% agree with the decisions and judgment calls; others, you’ll honestly question. And that’s okay to have questions. It’s our job as educators to ensure we are diligent and working in the best interest of our scholars. However, even though we may have questions at the end of the day nine times out of 10, we still must stick to our prescribed pacing and standards alignment.

When I was teaching fourth grade, one of the first math units I covered was multiplicative comparison. When I first saw the unit and the types of questions I was having to help students work through, I was floored. How in the world was I supposed to teach multiplicative comparison without students first knowing how to multiply? It didn’t make any good sense at all. However, the state gave checkpoint testing throughout the year, and our first test always had multiplicative comparison on it, with multiplication being expected to be introduced before a different checkpoint later in the year.

In the first year, my students didn’t perform well on that skill at the first checkpoint. I mentally shrugged it off and pointed the blame at the fact that teaching a multiplication skill without teaching how to multiply as a skill was a fool’s errand and that I had done the best I could.

Reflecting on that experience now, I realize that I, as an educator, had failed to take the time to really dive deep enough into my standards to understand what was being asked of me to teach and to set my students up for maximum success.

The underlying goal of teaching multiplicative comparison (and additive comparison) at the beginning of the school year was to help foster a mindset and way of thinking when it came to comparing objects using different operations. My goal should have been to help students know how to identify comparison word problems and what kind of comparisons were taking place. The actual skill of multiplication had been formally introduced in third grade, up until a specific range of numbers, so as long as my numbers remained small enough, my students had all the tools they needed to strengthen this thinking at the beginning of the school year.

It also served as a review unit for the multiplication they learned in third grade to help make sure that skill set was still practiced before you reached fourth-grade multiplication with larger numbers and other multiplication strategies being introduced.

By not working harder to ensure student success with that standard from the beginning and instead intending to integrate it into my end-of-year review time after multiplication had been properly taught, I robbed my students of almost an entire year of exposure to and practice with a whole type of word problem.

It seems wild to see it put so bluntly when, at the time, it seemed like such a small, inconsequential choice in the scheme of teaching.

It’s important for us as teachers to remember that even when our pacing seems haphazardly thrown together, there is typically a rhyme or reason for why it was laid out the way it is.

When we find ourselves questioning the curriculum or the standards, it’s more beneficial to direct our questions reflectively towards the areas we can control. Instead of focusing on the perceived injustice of the standards or the changes we would prefer to make, it’s more productive to consider how we can best implement the standards to benefit our students.

Some questions that can be helpful to help guide your reflection are:

- What is the goal of this unit?

- Is the skill being introduced for the first time, maintained from previous years’ instruction, or developed further?

- What did the stairstep standard from the year before look like?

- How does understanding this skill now impact student learning throughout the rest of this year?

1. What is the goal of this unit?

Knowing the unit’s goal, you can peel back the layers of the unit to see the critical part. For example, going back to the multiplicative comparison, the important part at that time wasn’t that students could multiply large numbers like the fourth-grade multiplication standards wanted later in the year, but rather the goal was that students developed the thinking of recognizing a comparison of a group of objects versus two singular objects, and what to do with that knowledge to set up an equation and solve.

This goal meant I could use the smaller third-grade numbers to build their thinking. As their ability in multiplication expanded throughout the year, that thinking could also be built upon with progressively larger numbers, but I wasn’t starting from the ground up.

2. Is the skill being introduced for the first time, maintained from previous years’ instruction, or developed further?

There is a huge difference between teaching a skill that has never been introduced at all, like division, in the 3rd grade after students do not have exposure to it in K-2 at all and teaching addition or subtraction in the fourth grade, where students have been taught how to add and subtract, just not with numbers that large.

Your expectation for student mastery will also vary depending on whether you know that this skill is a maintenance skill or whether you’re introducing it for the very first time, and students should have no prior knowledge of how to solve it.

3. What did the stairstep standard from the year before look like?

When it comes to being a proficient teacher, you need to know your grade-level standards in depth and be cognizant of your vertical alignment. What your students should already know before coming to you, as well as what they will be trying to add to your standards when they move on from you, are essential to be aware of when you consider your instructional approach.

When considering skills that your students should already know before coming to you, it’s also relevant to understand what strategies should have been taught to them to solve that type of problem. For example, in my state, 4th graders learn to divide numbers up to the thousands place, but a single digit divisor. However, they aren’t taught long division as a strategy to do this at all. So if I were a fifth-grade teacher, and I didn’t fully understand what my students should have been taught the year previous, I would likely assume that students know how to divide using long division up to the thousands place and that it’s my job to teach them division with decimals, as well as division with numbers larger than the thousands place, or numbers being divided by a two-digit divisor. I would try to get started immediately without first teaching long division because of my faulty assumptions about student knowledge from the previous year.

Talk to the previous teachers if that’s an option. Look closely at the standards (an unpacking document can be particularly helpful if your state provides it). You may even want to discuss with your school or district math coach some of these standards and how they work together to ensure that you fully understand how each year’s standards build upon each other.

4. How does understanding this skill now impact student learning throughout the rest of this year?

Why might it be beneficial to know this skill at the beginning of the year versus the end of the year? Are there other skills throughout the year that will hinge or build up from students’ understanding of this particular skill?

Ultimately, the better you can understand the standards and expectations for your students, the better you can teach them because you fully understand the road map they are intended to follow.

Time and exposure are often among the greatest factors in your knowledge base of the standards’ expectations but taking the time to really ask questions about what you’re trying to get out of the different standards and their pacing and alignment will help ensure that you are planning for optimal student success throughout the year.

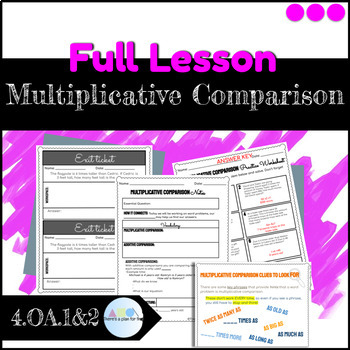

Teachers if you read all of this and still are walking away feeling irritated about multiplicative comparison being taught at the beginning of the year before multiplication, I have just the thing for you. Head to my tpt shop and check out my Multiplicative Comparison slideshow lesson, complete with formative assessment checkpoints, printable notes for students, and even a practice worksheet for independent practice.

Leave a comment