One of the cool things about many of the current philosophies in math instruction is that there is a real emphasis on multiple possible strategies to find a correct answer. With that belief, there is also an increase in breaking down math into building blocks that progress upon each other.

As a new math teacher, one of the things that I quickly realized was that my college introduction into common core math, wasn’t sufficient in covering all of the different strategies that I needed to be able to teach my students to help them succeed. In fact, during my very first year of teaching I actually got confused on the expectations for the grade level instruction, and taught long division in 4th grade, since that was what I had been taught when I was a 4th grade student, when in fact that wasn’t even supposed to be addressed until the next grade level. (Oops– my kids did do great in 5th grade when long division was “officially taught” however.)

Any who, moral of the story here is don’t be like me. Make sure you really look at the expectations of the standards you are teaching and address the key points that need to be taught.

Today I wanted to dive deeper into a potential division strategy that I taught to my students (after my first year) which they had great success with, partial quotient division.

Don’t forget to stay tuned until the end as I’ve got a free poster handout that can be shared with parents to help them understand and support this strategy from home as well!

The idea behind this strategy is really fairly self-explanatory, we are going to do division that focuses on finding smaller answers to division problems and using those pieces to find the total answer.

My favorite thing about this strategy in particular is that many students find success in it, as they really only need to have mastery over basic multiplication concepts, (x1’s, x2’s, x5’s, and times multiples of 10’s), as well as basic addition. If students can do that, then they can successfully work through this strategy, which for many students is empowering.

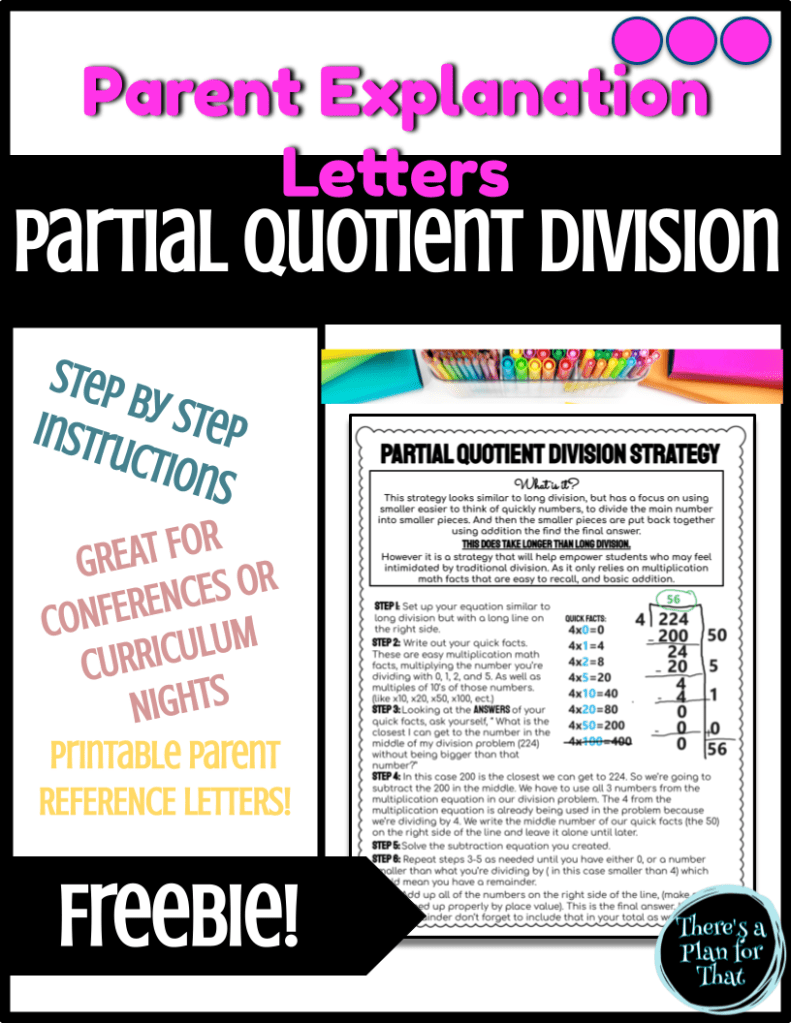

The very first thing you do with this strategy is set up your problem like you would write any division problem to solve using long division, except you have a long line drawn at the end of it on the right side of the problem. An example of this is shown in the picture below.

Next students will write out a list of quick facts. Now it is important to note that which facts are expected of quick facts can vary depending on teacher to teacher, I have even changed some of what I expect students to write out regarding quick facts as I grew as a math teacher as well.

The facts that I found to be most useful, and easily understood by students were:

____x0=_____ (I used this one because it helped students know for sure they were finished)

____x1=_____

____x2=_____

____x5=_____

Once we have those core facts, we can use them to help generate the answers for the next set of our quick facts, because the rest of our quick facts will be multiples of 10’s based off of these numbers. So they would look like:

____x10=_____

____x20=_____

____x50=_____

____x100=_____

____x200=_____

____x500=_____

____x1,000=____

It is important to note that our quick facts could continue along this pattern as large as we needed it to. In the case of the example which we have going right now we have 224÷4. I know by looking at the number that we won’t need the x500, or x1,000 category because those are bigger than what we are dividing, and our job is to only look at pieces. The quick facts that I would use specifically for this example would look like this.

4×0=0

4×1=4

4×2=8

4×5=20

4×10=40 (notice this is the same as 4×1, but with a zero added to my answer)

4×20=80 (again this is the same as 4×2, but with an additional zero)

4×50=200

4×100=400 (I stopped quick facts here because I know that 400 is already bigger than I needed to solve.)

As a teacher, the writing out of the quick facts is something that can eat up a lot of time. I have found that having a day where we write out a master chart of our quick facts that we keep inside of our math notebooks/folders/binders (wherever you expect your scholars to hold onto their math notes at) has been helpful! Typically, we would have some class time where we would work on this, and then it would be part of the take home expectations for the students to complete.

Now that we have our quick facts, we are ready to solve. Looking at the ANSWERS from our quick facts we need to ask ourselves the questions, “Which of these answers is the closest we can get to 224 without being bigger than 224?” We want to start at the bottom of the list.

In this case 400 is too big, as it’s already bigger than 224, so we want to cross that out. Our next largest number is 200, which is smaller than 224, but as close as we can get with our facts, so that’s the number we want to use. We’re going to write that number underneath the 224 in our original problem and set it up as a subtraction equation. Like this.

Next on the right side of that long line, next to the 200, we’re going to write the middle number from our quick facts’ equation. We used the 200, so in this case we want to use the 50.

Now we’re going to solve our subtraction equation and see what our new number is to work with.

In this case our new number is 24. Looking back at our list of quick facts we’re going to ask ourselves the same question as earlier, “How close can we get to 24, without being larger than 24?” Any of the larger numbers we can cross off our list.

It looks like the closest we can get to 24, is the quick fact answer of 20. So we’re going to write 20 under the 24 as our new subtraction equation.

We’re also going to write the middle number from our quick fact equation, 5, on the right side of that line. It’s important to remember that in partial quotient we can’t leave out any of the pieces of our equation. We always have to have the three numbers represented in our division problem (the 4 is always represented because we are dividing by 4 each time).

Again, we are going to solve our new subtraction equation we have created to see what our new number to work with is.

We’re going to repeat the same process with our quick facts as before. This time we notice that 4 can go into 4 exactly.

We know that we’re done using our quick facts when we either reach 0 as our total answer, or the number that is left to subtract can only be subtracted by the 0 quick fact because the 4 is too large. In this case, we have a 0 so we know there is no remainder to this division problem, and we can move onto the last step. Typically, as a teacher I would model subtracting the 0 quick fact anyways, because it helps students clearly see when a remainder is there in other division problems. So, I would repeat the process one last time.

Now that we’ve divided out the dividend into smaller pieces, it’s our job to reassemble those pieces to find the final answer. On the right side of the line, those numbers that were written off to the side then ignored while we were subtracting need to be added up.

One thing that I did notice with this step is that students often made silly mistakes due to numbers not being lined up properly. As you can see from my example above, the 5, 1, and 0 look like they’re lined up under the 5 in the 50, which is actually the ones lined up in the tens place. To help avoid this potential wrong answer I would always encourage my students to rewrite the numbers on the side taking special care to line them up properly. If I found they continued to struggle with lining the numbers up properly I would show them how to rewrite them using graph paper, to help them keep everything straight and in the write place value place.

Our final answer to 224÷4 is 56. With a remainder of 0 (or no remainder).

If you’d rather watch and see this strategy modeled for you in real time, feel free to check out this video!

It is important to note that this strategy does take longer than long division, which is what most parents are used to knowing how to solve. It also is set up similarly to long division, so this is one of the strategies that I’ve historically had the most push back from parents about.

One of the fastest ways for your students to fail at this strategy is to learn partial quotient in school, but have parents showing them long division at home, and kids mixing up the two strategies and ending up with a mix of both and a mastery of none.

What I’ve learned is that parents aren’t actually opposed to the strategy, it may not be their favorite, but the biggest reason they push back against it is that they don’t understand how to support it.

To help your parents understand, it can be super beneficial to show them how to do it. If your school has a math night, or a curriculum night, this is a GREAT strategy to model with your parents. Walk them through the process. Share this blog post with them, so they can see the step by step breakdown. Share the YouTube video that I have posted above! Providing your parents with an understanding of what you’re trying to teach the students, as well as a reference point to go back to and refresh themselves on the steps is one of the biggest ways you can empower your parents to help you, help their scholars!

I’ve included a free poster which you can print out and send home to parents to help explain what this new strategy is, as well as how to support it at home! To access your freebie in my Free Resource Library, make sure to join my email list to get the code for the free resource library. You can click HERE, or the picture down below to join my email list today!

Leave a comment