As a math teacher, one of the most frustrating conversations I’ve had with parents is about why a student who knows how to add, subtract, multiply, or divide keeps getting low scores on tests and quizzes covering those same skills. Parents are perplexed because they’ve practiced solving equations with their students over and over, making sure they get it right. And honestly, I can understand their frustration. There’s a big difference between knowing HOW to solve the four operations (addition, subtraction, multiplication, and division) and knowing WHEN to apply them.

One of the challenges with many math curriculums and classroom teaching methods is the tendency to teach skills in isolation. For example, when we’re teaching multiplication, we usually start by teaching how to multiply. Then we apply that skill to word problems where kids practice determining the operation and multiplying for the answer. Unfortunately, we’re not actually teaching them how to determine operations when we teach that way.

Let me emphasize this: TEACHING STANDARDS IN ISOLATION DOESN’T HELP STUDENTS LEARN TO DETERMINE OPERATIONS IN WORD PROBLEMS.

So when parents are confused about why the test says their child can’t multiply when they know they can, it’s because the child doesn’t know when to multiply in a word problem. They’ve only seen multiplication word problems in the context of a multiplication unit where they expected to see multiplication problems.

To address this, it’s important that, as teachers, we invest time in TEACHING how to determine operations and continue solving the four operations throughout the year. There are various anchor chart posters available on the internet that promote different strategies to help students. One of the popular ones is CUBES.

This is just a quick example of what I see when I run a google search for CUBES.

While I don’t hold a grudge against any of these methods, I’ve found that most of them, including CUBES, rely heavily on keywords to help students determine what to do in a word problem. The issue with this is that while keywords are a great strategy to use context clues, when students become too reliant on them, they get tricked as math becomes more complex. The keywords that reliably indicated addition in 3rd grade might not mean addition in 4th or 5th grade math. Relying too much on keywords can be a long-term handicap because it doesn’t teach students how to THINK about math; it’s just a quick fix.

Personally, I tend to deviate from the more traditional, pretty anchor chart word problem strategies. I’ve found that having a predictable problem template and a series of guiding questions help break down the process of figuring out what to do with word problems.

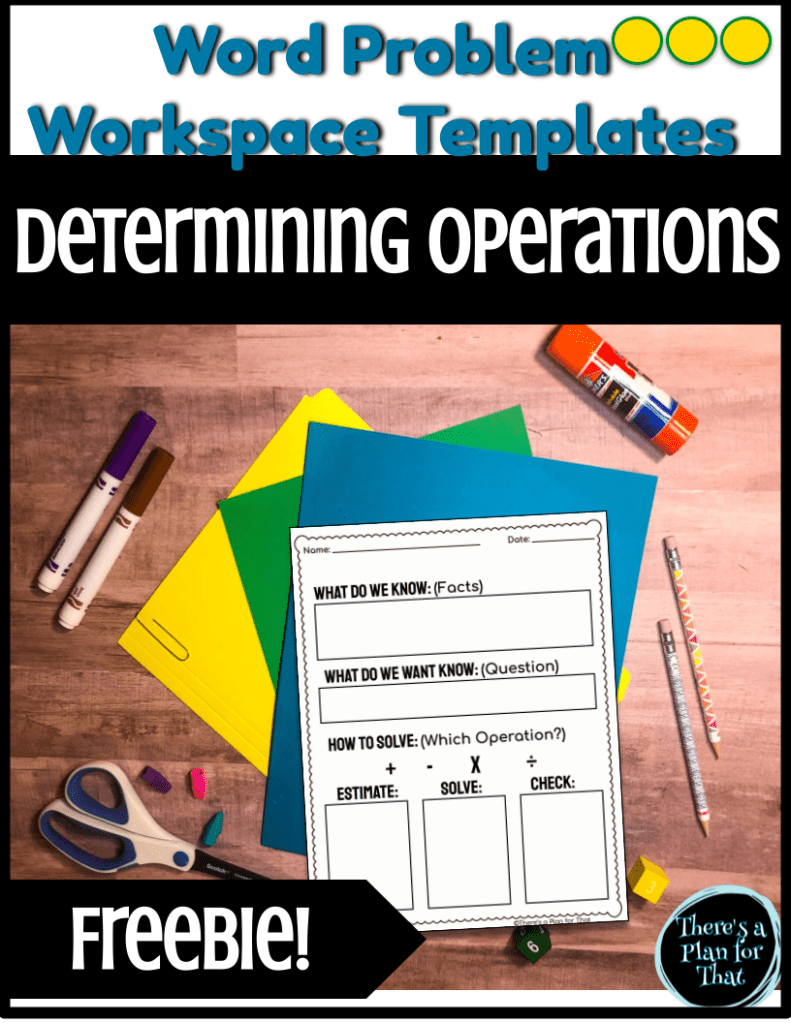

I’ve had so much success with my word problem template that I’m sharing a copy with you today. Don’t forget to grab your download from the Free Resource Library! P.S. the library is password protected so you will need to join my email list to get your exclusive access to the passcode!

-When we encounter a word problem, the first thing we do is write down what we know. These are the facts given to us in the word problem.

-Next, we write down what we want to know, which is what the question in the problem is asking for. If there is no question, then we know it’s not a complete word problem because a word problem needs to ask a question to let us know what we’re trying to do. I talk about this especially at the beginning of the year, especially if I ever have students create word problems for each other to solve.

-Once we’ve written down the facts and the question, we have to determine the operation. To figure out which of the four operations to use, we start by picturing the problem like a movie playing in our heads. Then we ask ourselves two questions.

- First: Should the answer to the question give us a bigger number or a smaller number than the numbers given in the problem already? In other words, do we already know the total? If we’re expecting a bigger number (or don’t know the total), we can eliminate subtraction and division. We only get bigger numbers when we are combining things together, like with addition, and multiplication is another way to say repeated addition. If we’re expecting a smaller number as our final answer because the total was given to us as one of the facts, then the opposite is true, and we can eliminate addition and multiplication. We only get smaller numbers when we are taking away, like with subtraction, and division is another way of referring to repeated subtraction.

- Second, the next question we need to ask ourselves is, “What labels do we have to work with?” When we think about a problem like a movie, if we’re talking about red beans and blue beans, and the question wants to know how many beans are there altogether, we can reasonably combine the blue and red beans into one container and have a container of BEANS. We could also take away from that container of beans to figure out how many blue or red beans there are. What we cannot do is add or subtract blue beans and packages of beans to find out how many beans are at a factory. A bean put together with a package doesn’t give you a total of beans. Your label can’t change that way.

To summarize, if you can reasonably combine or take away from the existing labels and still answer the question with the specific label it’s asking for, then addition or subtraction is the right operation. If your labels can’t be combined or taken away in ways that make sense with the label from the question, you’re dealing with an equal groups situation, which means you would be using either multiplication or division. By asking these two questions, you’ve figured out which operation to use.

-Now that you’ve determined the operation, my students fill out an estimation box where we round the numbers, typically to the nearest 5’s, 10’s, or 100’s, and solve with the operation we determined in the last step.

Is this step unnecessary for finding the exact answer for that specific problem? Yes, it is.

However, I’ve found that it helps create stronger math scholars in several ways. One, it provides them with more exposure to rounding, a skill students struggle with in upper elementary. We don’t have enough time in our curriculum pacing to give it the time it needs for full mastery. Two, it helps students catch their own mistakes and eliminate misleading answers. Our rounded answer gives us a basic idea of what kind of numbers to expect in our final answer. If our final answer and our rounded answer are completely off, it can be a sign that we need to recheck our work.

-After we’ve rounded, we get to solve our actual equation based on the numbers provided in our facts and the operation we’ve chosen.

-The last step is to check our answer. One way to do that is using the inverse operation, which means the opposite operation (like the opposite of addition is subtraction, and the opposite of division is multiplication). I include the vocabulary word “inverse” when discussing this, and it takes some modeling before students can fully do this independently. Continued exposure to the vocabulary and the skill can be highly beneficial to students as they progress in their math education. Using repeated addition or repeated subtraction is a way to check multiplication or division, but I encourage my students to use this strategy the least. The more you have to repeat an operation, the more likely you’ve made a mistake somewhere in your math. Also, as you advance in math, the numbers get bigger, so while repeated subtraction isn’t too bad for 47 divided by 7, it can be frustrating for 4,907 divided by 7.

If this sounds a bit confusing, check out this video I made that walks you through all the concepts discussed in this blog.

If you just want to check out the modeling of the problem, skip ahead to 3 minutes and 45 seconds to skip the introduction.

Please note that for the sake of time in that video, I didn’t model the estimation part of the word problem strategy, but if you’d like to see it, leave a comment below, and I’ll follow up with another blog post about it!

Remember that you can use all the best strategies to teach determining operations in word problems, but without repeated consistent exposure, it won’t stick for most students. So, it’s essential to find a way to integrate this into your math routine.

I’ve found that a “problem of the day” approach is very helpful. In my “problem of the day” routine, I let students solve a problem in their notebooks independently using the elements and components I’ve described above. Then, we check the answers together as a class.

At the start of the year, I facilitate the checking, working through the problem on the whiteboard. As the year progresses, I release some of the responsibility to the students, choosing a “leader” to help us check our work. In the beginning, I intentionally choose students who are more confident, but as time goes on, all students become more comfortable, and I call on those who may be less confident. It ends up being a huge confidence booster because students have seen so many problems by that point, and they surprise themselves with how well they do. It’s heartwarming to watch the scholars encourage each other through stage fright and any mistakes they might make.

Don’t forget there’s a copy of my word problem template in the Free Resource Library, waiting for you! Join my email list to get access to the code so you can download it right now. Click the link below to join my email list. ⏬⏬⏬

Leave a comment