Think back to your very first year of teaching, or maybe you are currently experiencing your first year of teaching. Either way, reflect on your very first review game that you played with your class. Personally, my first review game was Jeopardy! I was so excited to find one; I searched TPT until I found the ‘perfect’ game for my students to review on a study day before an assessment. I was genuinely more excited than the kids. However, by the end of the review game day, I was over it. I swore off games in the classroom and vowed to use only independent review study guides.

Thankfully, someone talked me down from the ledge and convinced me to give games another try. Some heavy reflection had to happen before I was brave enough to attempt a review game again.

I’m here today to help you learn from my failure. To start, let me outline specifically all the ways our game play went south.

- I didn’t establish routines and procedures well enough to actually work – although I thought I had done it.

- Students were off-task during work time. Not all of them, but the same students were off-task each time.

- I let students have free rein over who was in which group.

- Students became discouraged when it became apparent that their team wasn’t earning enough points to stay competitive.

Now that I’ve told you how it didn’t work, let’s unpack them and look at some things I could have done or have since added that have allowed my classroom game play to do a complete 180 flip!

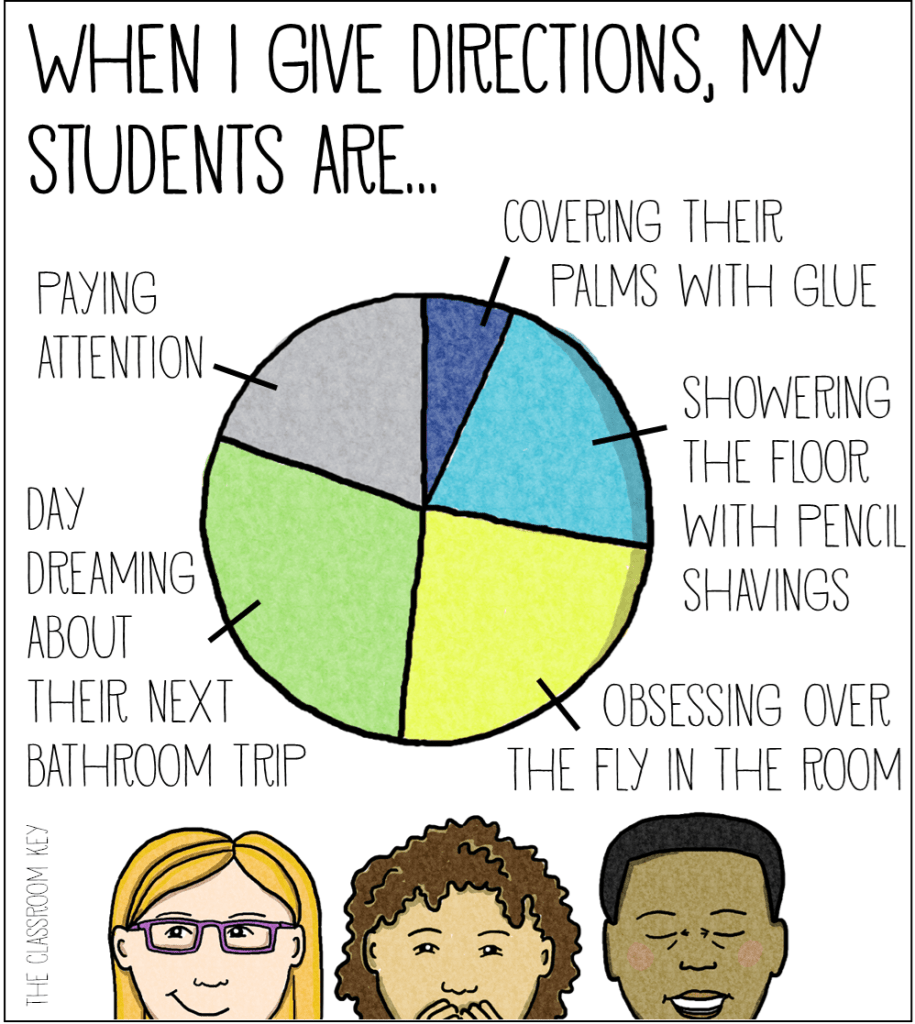

1st issue- Routines and Procedures: Whenever you introduce something new, you have to model and practice your expectations. At that point, I still believed that I could read off the directions – a whole list of them – and then expect all of the students to be able to follow them and us to get started without a hitch.

I didn’t provide enough breakdown of my directions. Instead of reading all directions at once, it’s better to group the kids together in their groups (I expand more on this later in the blog post) and then give one-step directions at a time, modeling each new step with a “practice” round.

One of the things I struggled with when it came to procedures was figuring out how to rein the kids’ energy and enthusiasm back in before it got out of control and I just ended the game out of frustration. (If you’ve ever had the luxury of playing Kahoot with students – you know exactly what I’m talking about.) I never wanted to fully take something away, but often felt like there was no leverage or “threat” I had to keep the kids in check.

You don’t need a “threat,” but natural consequences are real. Before diving into any exciting activities, it’s important to outline your expectations. If you’re in a CHAMPS classroom, you would C.H.A.M.P. it out. If you’re not and have no idea what I’m talking about, essentially, I’m saying you would establish your expectations for all aspects of student behavior. How and where they move, how we communicate, what volume we would expect, and where our attention should be. Discuss all the details of your expectations. (Check out last week’s blog post HERE to dive deeper into CHAMPS.)

The problem for me is that I would review my expectations, but failure to meet them would be met with “the game is over.” I didn’t want the game to be over. Let’s face it; if your lesson plan says today we are playing a game… Well, today we’re playing a game. There is no Plan B, and coming up with one requires additional work on the teacher’s behalf. Nobody has time for that.

Creating a warning system was a game-changer! Now calling it a warning system may make it sound fancier than it actually was. I simply picked a word and wrote it on the board. Typically, 5 letters or less; 4-letter words were the sweet spot. Too many letters and the kids would think they could get carried away for too long without consequences. Every time the kids failed to meet the expectations set, we would lose a letter. Every time we lost a letter, we stopped and reviewed our expectations for game play, specifically focusing on which part we were doing incorrectly and what behavior was expected instead. Then the game would resume. If all the letters were erased from the board, the game ended. Regardless of whether it was finished, the game ended, and our study session converted to an independent, much less exciting way to review information. I also found that incentivizing keeping letters was a game-changer! If we kept ALL of our letters, then we might earn 5 minutes of free time at the end of the day, or something added to a classroom reward system, or an extra brain break during our lessons later on. You know your kids, and you know what incentives would be a great fit for them. If they only lost 1 letter, I would also offer an incentive, although not as great of an incentive. Any more letter losses and there was no reward for our behavior, other than the game continued to play. Pro Tip: Good behavior can EARN BACK LETTERS! Yes, this may seem counterproductive, like the kids messed up, we should hold them accountable. But honestly, if they are actively working hard to earn them back, that means they are behaving exactly as you were expecting them to. You’re winning; let them earn the letter back and show you that they can follow directions and work properly.

2nd Issue: Certain Students Are Off Task: Whiteboards and independent work time will be your best friend in this department. When you have a new problem on the board, the expectations should be that for the first 30 seconds, ALL students are solving it on their boards. Not just the person answering it, not just the team who picked the question – all students. Then the teams should have collaboration time, where they talk through their different ideas and answers and come to a consensus. You can still have one speaker elected for that round, but that person should be representing the voice of the group consensus, not just a single student’s answer.

Expecting all students to solve the problem makes the game more rigorous and a better use of study time because, let’s face it, a student solving 2 problems in an entire hour has wasted almost an hour. But that same student solving 25 problems in an hour, even if they didn’t get the chance to share their answer out loud with the entire class, their brains have been engaged and reviewing information non-stop. It’s a much better use of time. It also forces students who would typically choose to opt out to be present and working. The key to having this strategy work is to be moving around the classroom during work time.

If you as the teacher get up at the front of the room and never leave your desk, little Johnny in the corner of the class is drawing pictures on their whiteboard instead of actually solving problems. By walking around as students work, it helps increase accountability because students feel more pressure that they may be noticed if they are off task.

If you do find that some students persist in doing off-task things, think of natural consequences. Maybe they lose the privilege of a whiteboard during this game. Instead, they will be expected to show their work on paper and turn that copy in at the end of class. Perhaps a participation score is attached to this activity.

If the paper doesn’t have work written on it by the end of the study session, you may want to follow up with that student’s guardians. It could be a quick phone call, email, message, or note to bring to their attention that there is an upcoming assessment in the class, and their scholar squandered part of their review time being off task.

Almost all students stop trying to get around the system when they realize they will be held accountable for doing the work regardless. Staying consistent in keeping the kids accountable will help them understand the expectation and allow them to remain on task during the game.

3rd issue- Free Reign Over Group Choices: I’m a big believer in students getting to pick partners and groups because learning how to make wise decisions in our choices can be a great learning moment. For example, I may love spending time with my best bud, but I may have a difficult time staying on task when they’re sitting next to me. A wise choice would be for me to partner with someone else, even though I’m allowed to work with anyone because I want to be able to get my work done properly. Now, this concept is something that is only developed over time, through repeated conversations and accountability checkpoints.

However, none of this is relevant when playing group games. And here’s why. You want to make sure that your groups have more mixed ability levels. You don’t want students to match up with all your more capable students in one group and your struggling scholars in other groups. It causes frustration, and ultimately the goal of studying is for the students to be learning from their peers and the questions they are working through. If everyone in the group doesn’t know what they’re doing, they can write out their work on whiteboards all they want, but the conversation part where they huddle together and vote on the answer isn’t actually helping the students to learn anything correctly and is therefore a waste of time.

Set your kids up for success socially, as well as maximize academic learning value of your games, and strategically place students by different ability levels in groups. Also use this as an opportunity to be intentional about where you place students who struggle to get along with each other. If you know that Student A and B argue every time they sit next to each other, it may be wise not to have them matched together in the same team.

4th issue- Frustration and Disappointment Over Clear Winners: The solution to this one is both the simplest part of this whole blog and the best part. If you’ve managed to read down this far, you’ve got a real treat with this one! At the beginning of the game, tell the students that the winner of the team is EITHER the team with the most points, or the team with the least amount of points. Nobody knows which one is going to be the winner until the game is over. Then pull the answer out of a hat (most or least). If you don’t have a hat, you can use an electronic spinning wheel on your computer to see which team wins (wheeldecide.com is a go-to website in my classroom for this). Click HERE and save this wheel that is already set up if you’d like!

By not knowing if you want to have the most points or the least points, it evens the playing field. Just because you’ve got the “smartest” people on your team doesn’t guarantee a win. That knowledge helps kids to keep their heads in the game. Ultimately the objective behind playing a review game isn’t to reward a team for being knowledgeable and getting answers right. The whole point in a review game is to help as many students as possible prepare for an upcoming assessment. Having students engaged is the way to go, not angry and frustrated halfway through the game because they’ve already decided it’s a loss.

Hopefully, these tips will help you run a class game as smoothly as possible! The nice thing about these tips is they aren’t specific to any one type of game but can be applied to a variety of classroom review games. The possibilities are endless!

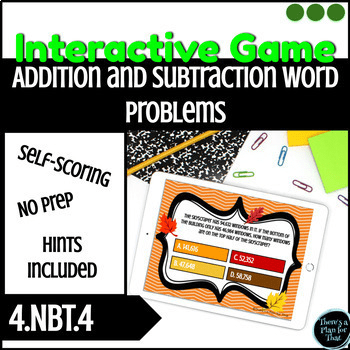

Now that you’ve got all these new ideas floating around in your head, you should head on over to my shop and check out some of my math review games! Designed for upper elementary students, my interactive self-checking games are the perfect fit for any classroom looking for a fun new game to try! They even offer hints as the students engage to help them learn from any mistakes they are making as they play!

Leave a comment